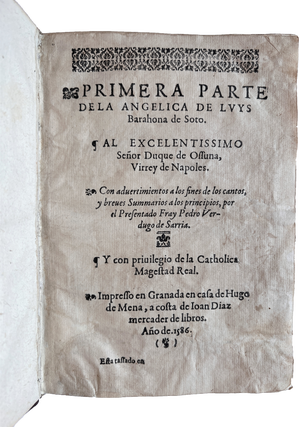

Primera Parte de la Angelica. Granada: Hugo de Mena for Juan Diaz, 1586.

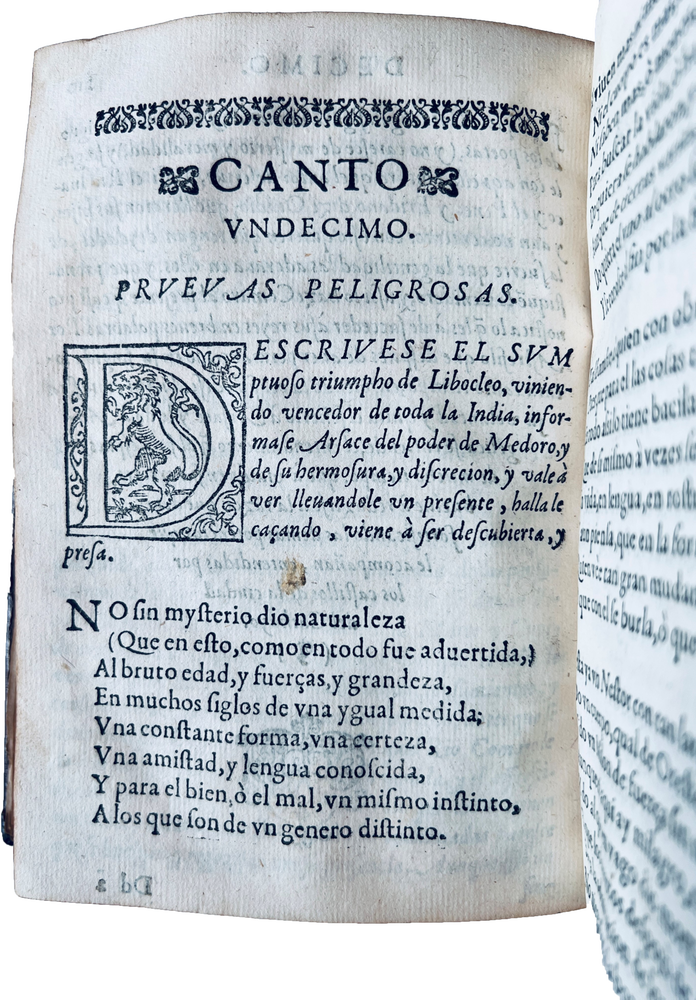

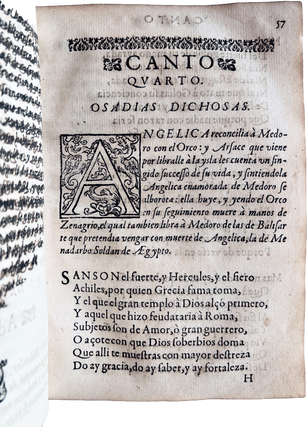

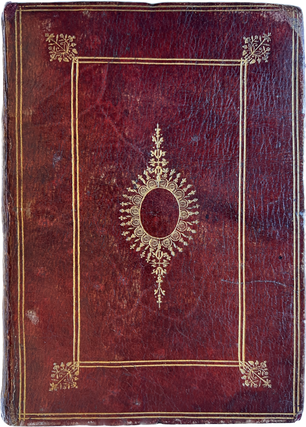

4to (183 x 130 mm). [4], 251 leaves. Woodcut initials opening each of the 12 cantos. The Advertimientos to cantos 2-9 and first 4 lines of that of canto 10 crossed out in ink, apparently by the same early reader who supplied stanza and line counts at the end of each canto. Title extensively repaired, the paper of first two quires rather thinned from washing and dampstained, scattered mostly faint dampstaining elsewhere. Seventeenth-century French(?) gold-tooled red morocco, covers panelled with two double fillet frames, at center an oval fan built up of small tools, flowering plant tools at corners of inner panel; sewn on recessed cords, smooth spine similarly panelled with double fillets, tiny fleurons at corners of inner panel, red-sprinkled edges, later (19th-century) endleaves and front flyleaves (repairs to head of spine, minor wear). Provenance: early ink markings and notations as above; James Patrick Ronaldson Lyell (1871-1948), green gilt morocco bookplate; manuscript notes on the edition in two hands, the first a series of citations (from Cervantes, Sedano, Gallardo, Salva and Ticknor), the second a description of this copy on a mounted leaf, signed with initials D.D.V.; with Libreria Bardón, sold in 2017 to: Kenneth Rapoport, bookplate.***

First Edition, all published, of an epic chivalric poem, praised by Cervantes and Lope de Vega (who wrote a sequel). One of the first works in Spain to be modeled on Ariosto’s Orlando furioso and Boiardo’s Orlando innamorato, the poem in 12 cantos, by a physician and, later, mayor of Osuna, expands on Ariosto’s tale of the Cathay princess Angelica and her love for the Saracen Medoro (the cause of Orlando’s wild fury). Barahona’s epic relates the adventures of the beautiful Angelica after her marriage with Medoro, her efforts to flee Orlando’s persecutions, her imprisonment, encounter with an orc, enchantments and other tribulations endured in her efforts to reconquer the reign of Cathay, seized by a rival queen.

The book was famously singled out by Cervantes, at the end of the priest’s book-sorting in chapter 6, Part 1: “The priest wearied of seeing more books, and so, without further reflection, he wanted all the rest to be burned; but the barber already had one open, and it was called The Tears of Angelica. `I would shed them myself,’ said the priest when he heard the name, `if I had sent such a book to be burned, because its author was one of the famous poets not only of Spain but of the world” (transl. by Edith Grossman, Harper Collins 2005, p. 52). A 19th-century literary historian wrote of the Angelica that “all contemporaries, from Diego Hurtado de Mendoza downwards, swell the chorus of applause” (James Fitzmaurice-Kelly, A History of Spanish Literature (1898), p. 188). In the past century, Barahona’s poem has been widely studied and interpreted on various levels, as an example of complex imitatio, a parable of the perils of worldly life and manual for spiritual perfection (cf. DBE), a mannerist exercise, or, in a particularly fluffy deconstructionist vision, as a metaphoric enactment of Vesalian dissection (based, apparently, on the assertion that “Barahona the writer carries within him Barahona the physician” - Ganelin, p. 304).

But the Angelica may not have been as popular as these paratextual musings imply, for this was the only edition to appear until it was reprinted in a facsimile edition for Archer Huntington in 1904. It appears rarely in the trade; the last copy that I trace was offered by Bill Salloch in 1975. 5 copies are held by N. American libraries (Hispanic Society, Boston Public, Univ. of Arizona, Harvard, and Thomas Fisher).

In an interesting example of private censorship, this copy was inexplicably marked up by an early reader, who perhaps just wanted to count the stanzas and found the preliminary summaries to each canto so annoying that he (we shall assume) energetically crossed them out (the text is still more or less legible), running out of steam at canto 10.

IB (Wilkinson, Iberian Books) 1607; CCPB (Catálogo Colectivo del Patrimonia Bibliografico Español) CCPB000001731-0; USTC 334911; Palau 23550; Salva y Mallen, Catalogo de la biblioteca de Salva (1872), no. 1530; Catalogue de la Bibliotheque de M. Ricardo Heredia (1891-94) 2128; BM/STC Spanish p. 10. Cf. José Lara Garrido, article in the Diccionario Biográfico electrónico; Lara Garrido, Las lágrimas de Angélica de Barahona de Soto, Los mejores plectros. Teoría y práctica de la épica culta en el Siglo de Oro (Málaga 1999); C. Ganelin, “Bodies of Discovery: Vesalian Anatomy and Luis Barahona de Soto’s Las Lágrimas de Angélica,” Calïope: Journal of the Society for Renaissance and Baroque Hispanic Poetry, Vol. 6, Nos. 1-2 (2000): 295-308. Item #4204

Price: $5,500.00