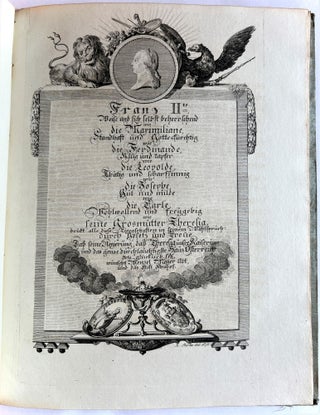

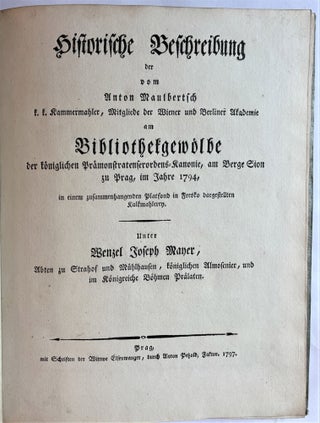

Historische Beschreibung der vom Anton Maulbertsch ... am Bibliothekgewölbe der königlichen Prämonstratenserordens-Kanonie, am Berge Sion zu Prag, im Jahre 1794, in einem zusammenhangenden Platfond in Fresko dargestellten Kalkmahlerey. Prague: widow [Barbara] Elsenwanger for Anton Petzold, 1797.

4to (262 x 204 mm). [14], 26 pages, printed on thick paper. Two engraved plates and an engraved text illustration, all by Johann Berka, woodcut head- and tailpiece vignettes and page ornaments. Contemporary blue satin over pasteboard, covers with gold-tooled scalloped and drawer-handle border, flower tools at inner corners, spine decorated with wavy line in black, gilt edges, block-printed sepia endpapers; covers lightly soiled, some fraying at spine and board edges, overall in fine condition.***

A fine copy of an important description of the painted ceiling of the new library hall of the Strahov Monastery in Prague, the Premonstratensian Abbey on the Pet ín hill, which still thrones among the picturesque edifices of the west bank of the river Vltava. This is the first edition in German; Petzold published a Latin version in the same year.

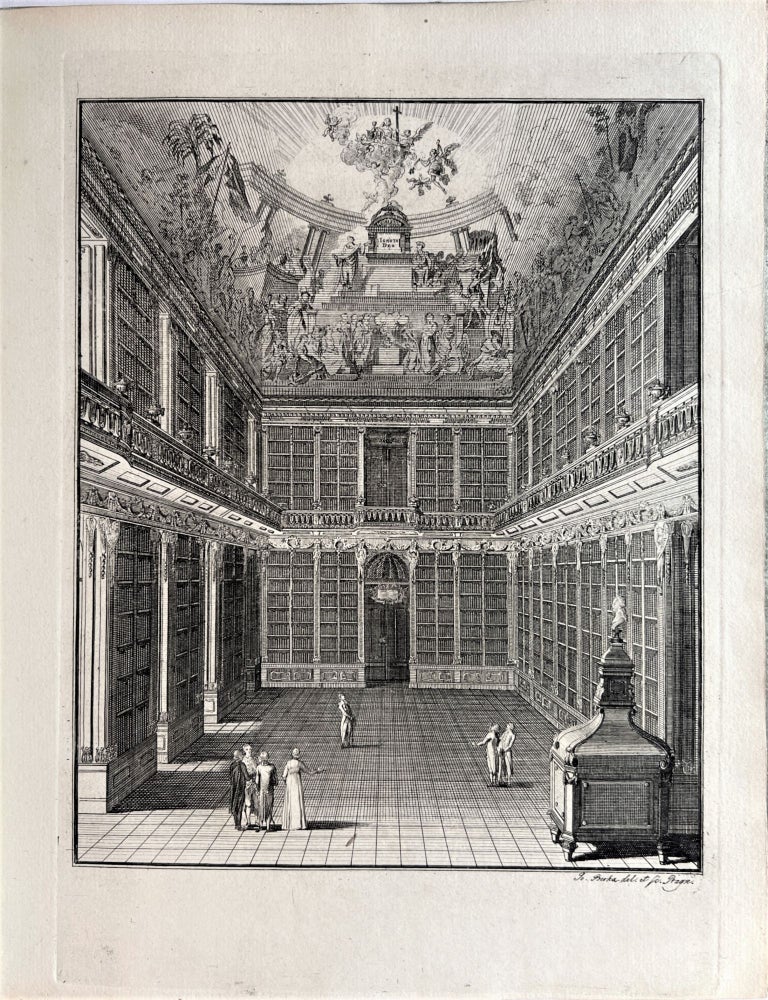

Called the Filosofický sál or Philosophy Hall, the vast new library building was commissioned by the abbot of Strahov, Wenzel Joseph [Václav] Mayer; designed by the architect Jan Ignác Palliardi, it was completed in 1790. It adjoins the original library, dubbed the Theological Hall (although both libraries ended up housing works on many different subjects), built in the 1670s under the direction of the philosopher-abbot Jeroným Hirnheim. During the succeeding century, a number of rebuilding projects had been undertaken, some necessitated by damage incurred by war. Mayer’s library was the last such major construction project. The immediate purpose of the new library was to house the collections of the Premonstratensian Monastery of Klosterbruck bei Znaim (Louka u Znojmo, in southern Moravia, referred to in this text as Bruck), which had been secularized by Joseph II in 1784, and whose library ceiling had also been painted by Maulbertsch. Along with the books came the magnificent walnut bookcases, shown in Johann Berka’s fine engraving. They are still in situ today, as is the imposing stove, and the principal subject of this short treatise, the allegorical ceiling painting by the celebrated Baroque painter Franz Anton Maulbertsch, whose many frescoes and a few altarpieces decorate churches and castles in Vienna and Lower Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, Hungary and Slovakia (many of these works are listed in the foreword). Maulbertsch embodied the last great flowering of Central European mural painting; after his death, the fashion for classicizing architecture and “a somewhat more restrained style of painting and a more subdued palette came into vogue” (Kaufmann, p. 431). His frescoes were characterized by brilliant coloration, thanks to the technique, then prevalent in central Europe, of Kalkmalerei, in which pigments were mixed with lime and water applied to dry plaster; he furthermore appears to have used impasto and a well-loaded brush. “Details of his frescoes seem from close up to call to mind features found in oil painting” (ibid., p. 430). Maulbertsch’s allegorical painting in Philosophy Hall depicts “the revelation of Divine Wisdom” (ibid., p. 453), or the “Intellectual progess of Mankind” (Strahov Abbey website). Painted in 1794 in only six months, with the help of a single assistant (Martin Michl) the magnificent fresco was Maulbertsch’s last important project; he died in Vienna in 1796.

The text of the Historical Description is believed to have been written by the abbot Václav Mayer himself (cf. Šeferisová Loudová, p. 90), although he is referred to in the third person throughout, and the work, dated October 4, 1797, is signed at the end by the canons regular of the Abbey. In the foreword the author eulogizes libraries generally in flowery terms, especially those publicly available to scholars, which he contrasts with private libraries, built for show. Moving to the particular, he describes the construction of the new Strahov Monastery library. Praising the abbot Wenzel Joseph Mayer (i.e., praising himself), the author describes his dogged pursuit of acquisitions for the library, needed in part to replace the many books damaged and lost through war (particularly under the Swedes, i.e., during the sack of Prague in 1648). So many were his acquisitions that Mayer ordered a new library to be built, with a separate entrance for the scholarly public. Above all he had the courage and determination (says the author) to make this library an exceptional space, the first step being his purchase, at great expense, of the splendid bookcases of the library of the dissolved monastery of Bruck. Since they were too tall for the ceiling as designed, the ceiling was simply raised. As the new library's crowning glory, Mayer hired the renowned painter Maulbertsch to paint the ceiling. The introduction concludes with an encomium of the young Emperor Francis II, to whom a marble monument was erected in the library, illustrated in Berka’s second engraved plate.

The text provides a detailed interpretation of the many figures and scenes and their meanings in Maulbertsch’s huge and ambitious allegorical painting. Biblical and Patristic figures, ancient philosophers (Aristotle, Diogenes, Heraclitus, Galen, Hippocrates, Socrates...), all gather in celebration of the progress of human knowledge, subsumed however under divine wisdom, the program “stressing the guiding light of religion over the recognition of the power of natural reason. The choice of this subject after the death of [Holy Roman Emperor Joseph [II] may be taken as a reaction to the Josephine Enlightenment” (Kaufmann, p. 453).

Scholars have noted that the textual descriptions diverge in many places from the actual painting. The Abbey's librarian Gottfried Johann Dlabacz left, in an unpublished manuscript, a more accurate description of the painting, which he appears to have written concurrently with Maulbertsch’s production of the painting. In fact, the present work, printed three years later, was conceived rather as a compelling literary relation of the intellectual-spiritual development of mankind, than as a guide to Maulbertsch’s painting itself. The edition was printed in 200 copies, all on fine paper, and copies were distributed to “professional artists and to members of sister monasteries” (Šeferisová Loudová, p. 90-91).

This pretty copy was bound in silk, clearly for presentation. The binding of the Anna Amalia copy, in dyed parchment, is similarly decorated. OCLC and KVK together list 8 libraries holding copies of this edition in Germany, Austria, Poland and Sweden; there appear to be none in US libraries (but 6 copies of the Latin edition). See M. Šeferisová Loudová, “`Historische Beschreibungen’ von Maulbertschs Fresken in Dyje, Louka und Strahov: einige Bemerkungen zur Beziehung zwischen Text und Bild,” in Ars 47, 2014, 1, pp. 84-92; Thomas Da Costa Kaufmann, Court, Cloister & City: the art and culture of Central Europe 1450–1800 (1995), pp. 426-430, 449-454. Item #4194

No longer available

Status: On Hold