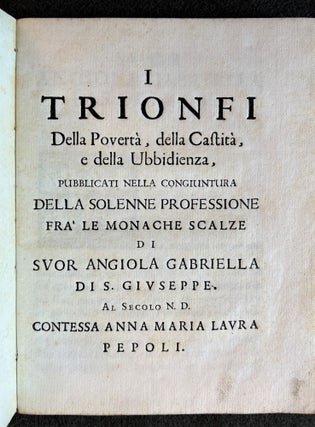

I Trionfi Della Povertà, della Castità, e della Ubbidienza, pubblicati nella congiuntura della solenne professione frà le Monache Scalze di Suor Angiola Gabriella di San Giuseppe al secolo N.D. Contessa Anna Maria Lavra Pepoli. Bologna: heirs of [Antonio] Pissari, 1699.

4to (190 x 145 mm). Collation: A12 B16. 55, [1] pp. Woodcut initials, headpiece above colophon on final page. Contemporary floral gold-blocked russet paper-covered flexible pasteboards (spine torn). ***

First Edition, a celebratory printing of three poems honoring the taking the veil of a Countess from one of Bologna’s oldest noble families. In 1698 the honoree Anna Maria Laura Pepoli entered the convent of the Discalced Carmelites in Bologna. The present collection celebrated the public profession of her vows. Indicative of her family’s prominence is the fact that this was one of four such poetic collections published in 1698 and 1699 to honor various stages of her monachization (see Frati, nos. 10036-10038), all printed by the Pissari heirs.

Unsubtly modeled on Petrarch’s Trionfi, which, states the poet and librettist Malisardi in his dedication to the Countess, “were composed for no other reason than to secretly praise his Laura,” the three poems, encomia both of the young woman and of the monastic vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, were composed, according to Malisardi, by three of his friends, who are not identified. In a note to the reader, Malisardi apologizes for any appearance of presumption in the bald-faced Petrarchan imitation. Monachization poems were, however, customarily Petrarchan, and this is no exception.

“As with marriages, one of the common features of monachization celebrations in the Counter-Reformation was the composition of poetry in honor of the spiritual bride. The outpouring of this particular poetic mode from the late sixteenth century in Italy has received little scholarly attention to date, perhaps because it appears almost like a form of ventriloquizing, as the newly enclosed nuns were effectively silenced by Tridentine reforms and their voices taken up instead in this commemorative, primarily male-authored genre.... Author’s names were not always included, but on occasion initials were given, hinting that total anonymity might not really be desired, or else that the poems circulated in a context in which the identities of the poets were already known. In the case of girls from particularly important or powerful local families, the celebratory verses might be collected into volumes, with contributions from a circle of writers.... [T]he particular convent was generally cited in the title of the poem, and thus the genre remains notably embedded in specific communities and locations. This transplanting of occasional Petrarchism, with its strong social and political overtones, into a devotional context in the seventeenth century is an example of the seemingly unproblematic redeployment of earlier sixteenth-century secular poetic practices in religious contexts during the Counter-Reformation. It also highlights that the most powerful and wealthy local families, those who would naturally attract the greatest number of socially motivated poetic tributes, were committing a significant number of girls and women to convents in the Sei- and Settecento, and that, as the cost of convent dowries rose, aristocratic social rituals came to dominate the space of convents. Thus monachization poems took their place alongside poems celebrating births, marriages, and deaths, representing an acceptable extension of aristocratic public networks” (Brundin, pp. 1127-1128). Such occasional poems were often read aloud or sung in the convents’ public parlors, and were sometimes even elaborately staged and set to music, as part of the boisterous social gatherings held by the families whose daughters or sisters were leaving secular life. These secular events held in religious spaces persisted throughout the 17th and 18th centuries in spite of repeated efforts by the Church to forbid them.

OCLC locates a single copy of this edition, at Harvard; ICCU lists 4 Italian institutional copies, in Bologna and Modena. The poems were reprinted in 1710 in an equally rare poetic collection, edited by T. Franzoni.

Luigi Frati, Opere della Bibliografia Bolognese che si conservano nella Biblioteca Municipale di Bologna, vol. II (1889), 10039; ICCU UBOE�31418. Cf. A. Brundin, “On the Convent Threshold: Poetry for New Nuns in Early Modern Italy,” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 65, No. 4 (Winter 2012), pp. 1125-1165. Item #4166

No longer available

Status: On Hold