Traité de l'Origine & des progrèz du Vertugadin. [Paris, 1733?].

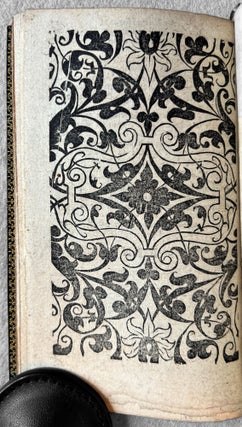

12mo (157 x 89 mm). Collation: A12. 23, [1] pp. Title with oval woodcut of a goddess with caduceus and hourglass, full-page arabesque ornament on last page, woodcut initials (one a factotum) and headpieces. Paper flaw at foot of p. 4 obscuring a few letters in note. self-wrappers and deckle edges. 19th-century jansenist green morocco, turn-ins gold-tooled, edges gilt, by Hardy-Mennil. Provenance: M. G., small 19th-century bookplate with Neptune emerging from a Viscount’s crown, shelfmark 331 supplied in manuscript; Paul Desq (1816-1877), red gilt bookplate (his sale, Paris 1866, lot 825); Dominique Courvoisier, DC bookplate. ***

A very rare humorous pamphlet, satirizing the use of farthingales, known as vertugadins in French: a series of hoops, made of whalebone, wood or wire, sewn into an underskirt to make it rigid, adding volume to the dress. (The term vertugadin was originally used in French by gardeners to refer to a kind of grassy mound.) Also called paniers (baskets), or jupes de baleine (whalebone skirts), what had begun in the 16th century as simple rolls placed around the hips had evolved into extraordinary armatures which dominated women’s dress styles for over 200 years. Some examples, for particularly great ladies, required the construction of special chairs.

Jokingly approaching this “vast subject, and even very vast, since it pleased our ladies to make them very ample,” the anonymous author traces the origins of this folly of fashion. Early theorists speculated that such “feminine cages” were modeled on the Tower of Babel, or on the Pyramids of Egypt, but our author traces the object’s origin rather fancifully to the 7th or 8th century, crediting the Moors, who brought the idea to Spain. Ruefully noting the contrariness of the fair sex, who ignored the orders of Charles IX (1550-1574) to abandon the practice, he muses that had the King made the hoops obligatory, the ladies would certainly have abandoned them. Its light-hearted tone notwithstanding, the piece is full of information, not least the many terms for both the farthingales and the women who wore them. Porte-paniers, swollen skirts, meteors, comets, fleets of sailboats ... the author paints a comical picture of a country bumpkin seeing an elegant lady in her barn-door-wide dress for the first time, and imagining that “women had become living barrels.”

After dying down for half a century, the fashion had flared up again in the early 18th century, with a vengeance, in skirts widened from the hips to the hems. The author records the spread of the most recent vogue through Europe: a German merchant having wrapped a bale of merchandise in one of the garments, it reached England, where it became the rage, eventually conquering the French court. By 1718 the style and its accouterments were “ratified by the feminine Senate of France.” The latest date mentioned is 1730, in which year a woman was apparently saved from drowning in the Thames by her giant floating skirt.

Why do women wear these things? To hide their bodies, perhaps certain midriff bulges (pregnancies)? Or perhaps to defend against that eventuality, by clothing themselves in veritable ramparts. The author, who is less misogynous than mocking of human folly, defends women, who can’t win, being criticized equally for excessively magnificent clothing and for dressing too simply. Besides, only a person ignorant of the extreme suppleness of women’s bodies, and especially of their vocal cords, and of the fibers of their tongues, would dare criticize them too harshly ... Men should not mock women for their excessive concern with their appearances, for what else is there for them to do? Let them join public life, from which “envious and jealous men have excluded them.” And what of men’s wigs? which hide many a flaw (and which today are “no longer just a coiffure for the head, but an envelope for the whole body”). In conclusion, the author reveals his true sentiments, which are that women should abandon the artifice, and be themselves; even if they look like spindles or sticks, it is more “glorious and useful” to return to the arms of nature.

The printing of this genuinely funny pamphlet was rocky. The compositor began with one type, but, realizing after a few pages that the text would overlap a single gathering, he switched mid-word to a smaller font. The lines are wavy. The signatures are idiosyncratic (fol. A3 is signed on the verso). But all is redeemed by the striking arabesque ornament covering the last page, which functioned, along with the illustrated title-page, as pretty “self-wrappers,” in which the stitched pamphlet was sold. Treasured by several bibliophiles, this copy appears to be one of two recorded; the other is preserved in the Institut national de l’Histoire de l’Art (Paris). Another edition, in 44 pages, is recorded (OCLC lists one copy, in Denmark). On p. 6 the author describes this pamphlet as a “piece fugitive, comme l’avant-coureur d’une autre dans un stile tout différent”: possibly a reference to the longer edition.

Brunet, Supplement, II:789, this copy; cf. Gay-Lemonnyer, III:1237 (the other edition). Item #4162

No longer available