Personal journal of a Parisian scrivener. [Paris, 1805-1807].

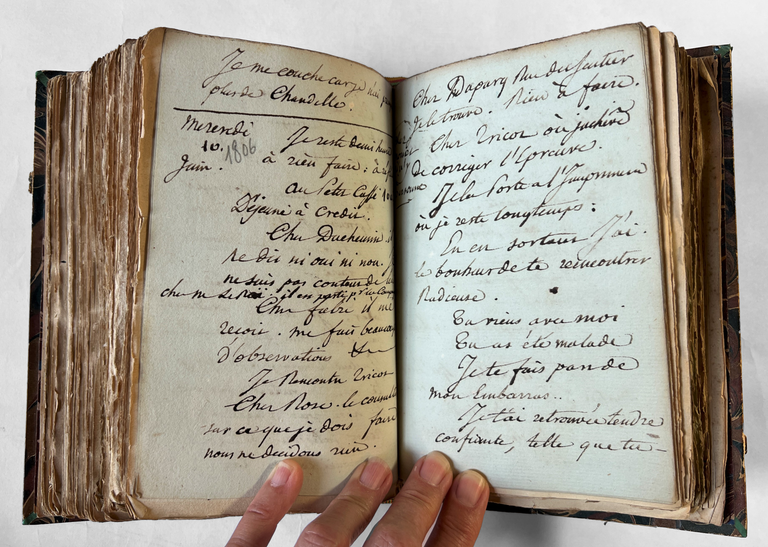

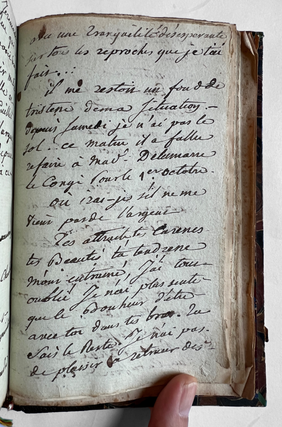

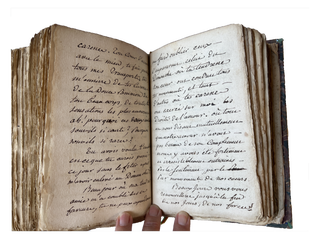

Manuscript on paper. 8vo (182 x 120 mm). [328] leaves including one integral blank. In French, in an irregular and mainly legible hand in brown and black inks, densely written, with deletions and frequent marginal additions, on rectos and versos, on various papers, some tinted. A later owner has added collational signatures in pencil (collation on request), as well as the dates in the Gregorian calendar, converted from the French Republican calendar which the diarist uses until the end of 1805. One leaf torn out leaving a stub (sinbce the signatures were added), several other lacunae, most indicated by blank leaves of wove paper supplied at time of binding. Some ink blotting toward end. Untrimmed, a few dusty edges. Early 20th-century quarter morocco and marbled boards, title gilt lettered on backstrip “Journal Manuscrit / 1805-1807.” Provenance: old paper backstrip, mounted on front flyleaves, with note “de la Bibliothèque F. Grilot”; clipping from a 20th-century auction or booksellers’s catalogue, above a trace of a removed clipping or bookplate; small modern book label with gilt monogram JCD. ***

Substantial fragments of an astonishingly intimate diary kept by a Parisian clerk during the first French Empire.

While the emotive focus of this highly personal diary is the writer's tumultuous and mostly painful love affair with a woman of higher social status, the entries cover the mundane details of his daily life (often a struggle to stay alive), from his repetitive and often poor meals, taken in the local bistro or in his attic home, to his constant search for work. The latter is intermittent at best, alternating periods of dogged labor, during which the writer often works from morning to midnight, with days of anxious pavement-beating seeking jobs. All this activity is not surprisingly punctuated by occasional days of paralysis and depression.

These 654 pages, from 1 September 1805 to 4 Sept. 1807 (with gaps) evoke the grueling existence of a member of the petite bourgeoisie in the early years of the Empire, a time of supposedly increased wealth, when wages rose faster than prices. Those who prospered were mainly the elite and entrepreneurs with capital, thus perpetuating in a different form the inequality of wealth and opportunity that was so glaring during the ancien régime. Most unusual here is the vehement and emotional tone of many entries, in which the writer records his thoughts and feelings, and even his dreams. Few such intimate personal records survive from this period, especially from a person of the working classes. “What little we can discover about the private feelings of people during the 1790s and early 1800s indicates considerable preoccupation, first with the revolutionary process, and then with the building of empire. … Those whose lives were more pathetic left little behind to tell the story of their private lives” (Perrot, ed., A History of Private Life. IV: From the Fires of Revolution to the Great War (1990), pp. 37-38).

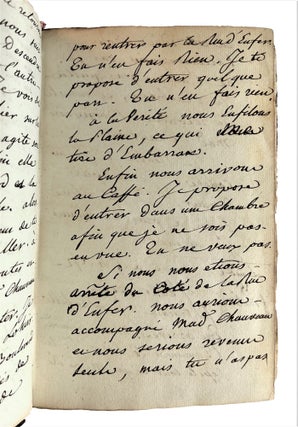

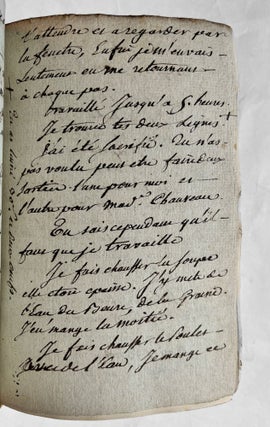

André, whose name is revealed only toward the end of the diary, lives from hand to mouth, notwithstanding the relatively high level of education required by his profession. Sicknesses come and go, hunger, cold and excessive heat. He records almost obsessively all his expenditures and meals, which during the lean times consist of bread and water. His daily or near-daily entries include often frantic lists of every person visited in search of work. The work itself, when he has it (mainly in 1806, with a lawyer or notary named Vuillemin), is only occasionally described, in the case of unusual mémoires or petitions to high government offices or officials, but the hours that he puts in are always noted: most days end at 11 or midnight, and they often begin at 8 am. He works in the boutiques or offices of his employers. That of M. Vuillemin is in the latter’s home, which is overly populated, in André’s view, by his annoying wife and teenage daughter, and is not far from André’s own garret, in the rue des Quatre Vents, near St. Sulpice, where he usually takes his mid-day meal.

The network of small urban trades plays a lively role throughout the diary. Besides his employers, mainly notaries and attorneys, but also simple folk who need help drawing up official documents, recurring figures include the blanchisseur (who launders his cravats), the cordonnier who repairs his shoes, a carpenter (who reglues the top of his walking stick), the milk-woman, his landlady, the indispensable perruquier (who, when André is flush, arrives at 7 am to “do his braid” and shave him, and who is fired for arriving late, and quickly replaced by another wig-maker found in the street), the pawnbrokers at the Mont de Piété, and his ravaudeuse, a woman prone to the bottle, who mends the clothes that he can’t cope with (he darns his own socks), and whose son is caught cross-dressing (see below). All these tradespeople, as well as those selling food and wine, are André’s perpetual creditors, and his most frequent note, besides “So-and-so has nothing [i.e., no job to offer],”is “Déjeuné à crédit” (dined on credit).

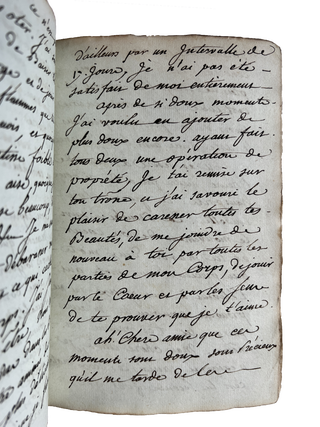

The heart of the diary, and perhaps his original reason for writing it, is André’s obsessive passion for a woman whom he addresses throughout in the familiar second person (tu). (Her surname, “Mad. Charles,” is mentioned in one of the last entries; the Madame implies that she is or was married.) He gives her his journals to read, and this one was probably intended for her as well. This does not appear to constrain his writing, for their sexual encounters, by far the happiest moments of his life, are described in detail, which, while not precisely graphic, is perfectly legible to an adult reader. Coitus, premature ejaculation (a frequent problem), orgasms, sexual satisfaction of his partner (which he is always attentive to provide), as well as wet dreams and masturbation, are all either lyrically described or alluded to throughout the diary. But overriding the sexual happiness is a profound sense of suffering, that of André’s possessive and perpetually frustrated desire to have and see more of her: it becomes quickly clear that this is an illicit affair, for he has a wife, from whom he is separated, and his probably younger lover is watched over by her brother, apparently her guardian, whom André loathes. She brings him money, which he accepts, reluctantly. Although the two do not live far apart, they see each other only in short periods, interrupted by weeks and months of absence – hers. Enervated by his frustration and longing, he reproaches her repeatedly for her “weaknesses” [for not defying the wishes of her brother and for bowing to social prejudices], for the feebleness of her reason, for using vulgar language (the only words that he repeats are the mild “vieux coquin”), for confiding in her servant Adèle, for her unreliability, her coldness, and her unwillingness or inability to verbally express her feelings. One imagines that he must have been quite overbearing, but there was clearly a strong attachment between the two.

Toward the end of the journal, in August 1807, André has concocted a plan which he hopes will bring him riches. Involving a “speculation at the lottery,” in his words, with an investment of 2400 livres (which he is trying to coax out of an acquaintance), it promises to bring in regular payments, in fact “100% every three months.” Whether or not this plan bore fruit is unknown, but the sober reader thinks not. A sense of hopelessness, due to André’s inability to support not only himself, but his estranged wife, and to his unassuageable longing for his lover, lends the journal an ultimately tragic tone, and the reader finds herself haunted by the acute sadness of it all, especially in the increasingly desperate last entries, when André is given notice by his landlady, and writes desperately, “where will I go if I can’t find money”? Like a post-modern novel, the journal ends with these words: “Ne pouvant rester assis, ni debout dans l’incertitude qui me tourmente Je me mets sur mon lit” (”Unable to stay seated or standing in the uncertainty that torments me, I sit down on my bed.”) One wonders, with dread, what happened to him.

This remarkable journal, a moving and rich slice of life, provides rare documentary evidence of everyday life in early 19th-century Paris. Here is just a sampling of these details: André lives in an attic, and cooks himself basic meals: panade (ground meat with bread), veal cutlets, chicory salads in spring, eggs, vermicelles (thin noodles), bouillie (gruel), always with bread and almost every meal with wine, but he also eats in the homes of neighbors or in local bistrots. He buys sugar and butter when he can, and occasionally uses tobacco. Sanitation is basic – he mentions seeing his lover go into an alley “to piss,”; and health above all is unstable: his lover is subject to frequent fevers, occasional boils, and an undefined recurring illness, treated with leeches; he experiences an injury or sprain of his heel, which he treats, unsuccessfully, with elderflower baths, suffering excruciating pain alone in his attic at night. Digestive problems are treated with flaxseed enemas; colds with orange water, licorice water, and sesame milk. The constant work, when he has it, is unhealthy: he becomes sick and depressed during a busy period, during which he barely eats: “L’ennui [et] la tristesse m’assiègent. Je me trouve mal, j’ai des envies de vomir, j’ai recours 2 fois à l’eau de Cologne et j’ouvre la fenetre de la Boutique. Je me repose. Jai toujours les pieds enflés sans douleur faute d’exercice.” (Boredom and sadness assault me. I feel ill, I feel the urge to vomit, I have recourse twice to Cologne water and I open the window of the office. I rest. My feet are always swollen without pain because of lack of exercise.)

Cold and heat are inevitable: in March they still cannot make love because of the continued “coolness of my slum” (la fraicheur de mon taudis). Candles are the only source of light, and André brings his own candles to his work: while his employer Vuillemin is a kind man, who treats him generally well, he is cheap, and André is sensitive to this. A recurring complaint is that someone (Mme Vuillemin, or her irritating brat of a daughter) has taken his candles. Paper is another frequent expense; it is mainly for “this journal,” and he notes one purchase of green paper, used in a couple of the quires.

André calls himself a “commis écrivain.” Essentially secretarial, his work involves taking dictation, transcribing, occasional calculations, drawing up legal forms, and, later in the journal, correcting printed proofs, whether directly for publishers or on Vuillemin’s behalf is not clear. Vuillemin gently criticizes his handwriting. If the journal, admittedly written unevenly, is at all representative, he must have been a mediocre scribe. Mistakes, which, at the beginning of his employ with Vuillemin, are frequent, require starting over; sometimes his employer yells, but usually he relents and is understanding. André is clearly grateful for any work that he has. Nonetheless, getting paid is a struggle; Vuillemin repeatedly short-changes him, on the grounds that he has no “small change,” and others take months to pay. “Je parle argent mais personne n’entend ce mot pour moi.” (I talk money but no one understands that word for me). When he does get paid, all goes to repay debts. From 22 livres in the morning, he is down to 3 sous by the evening. André records many brief vignettes of people, and a few more extended anecdotes. He is forced to see Vuillemin’s family daily, and records their spats and outright screaming matches. The wife is a goose, in his view; “may she go to hell,” he writes, all she talks about are “faces, clothes, complexion, fashion, figures,” and her daughter Mlle Eléonore is ignorant and loud; he can’t stand her grating voice. His view of the daughter is nuanced, however (and he records an erotic dream about her one night), as he blames Vuillemin for not providing her with an education. One day he goes to the “wine merchant,” buys a bottle of wine, rents a room [to dine] and invites his employer for lunch, during which he proceeds to lecture him on the need to educate his daughter before her life is ruined. Vuillemin concedes, but he is soft, too indulgent with his family; he adores his children (of whom nine were born, though apparently fewer survive), and by the end of the diary the situation appears unchanged. In July 1806 the writer notes that Eleonore has told his friend M. Rose that her mother is “an animal who is teaching her more evil than strangers would, that she beat her and got her father to beat her, and that she would rather be a streetwalker than live like this.”

André’s attitudes toward women are enlightened, his misogynism being mainly of the unconscious type that pervaded society. He places great value on education, remarking a few times that such and such a client is “instruit,” or that a friend is intelligent and would have benefited from more education. He clearly has defied the social norms of his time, separating from his wife (whom he sees occasionally by necessity, and speaks of without animosity), divorce having been made almost impossible in 1804 with the establishment of the Civil Code (after its temporary liberalization after the Revolution). It seems that he supports his wife, or tries to: her current lodging with one Mme Jarry being threatened, he advises her to go the quartier of the Louvre to find a cheap room, even though he can’t promise anything [any money], but she should look for something first and then “one” will find a way to pay for it.

Other brief portraits include that of his friend Monsieur Rose, a laborer who is under the thumb of his tyrannical wife; his neighbor Tricot, apparently a bistro keeper as well as a tailor; various female neighbors; and Vuillemin’s visitors, including one Danisy, “of noble origin,” who “has nothing to do and spends his days killing time,” and M. Blanchard (evidently a member of the publishing family), who is educated but who speaks slowly and pompously, and “talks talks talks,” about the revolution, for example, “which he only witnessed from afar.” On 14 February 1806 André records the topics of a conversation between himself, Blanchard, and Vuillemin: “Protestants / Heresy / Sun / Light / Electricity / Galvanism / Jews.” He works also with the bookseller [Pierre] Gueffier, trying to set up a deal with Blanchard, correcting proofs, and later acting as general gopher (in the last entry he brings “books from Aubert to be bound”).

André helps his poorer neighbors, and ends up with a circle of friends of the lowest social classes, whom he describes affectionately. In an entertaining interlude he relates the tale of his neighbor the ravaudeuse (mender), and her family woes: this lady, who is wont to take a drop too much, confides in André one day that she has problems with her 18-year old son, who is living with a woman in the rue des Canettes and refuses to talk to his mother. The day before, after drinking, she went there and said “stupid things” to the woman. André advises her to go to the police to try to get information on this woman. She decides not to, blaming herself for her son’s rejection. A couple of days later, trying to help, he visits the son, and finds the two cross-dressed: “je les ai trouvé à table, son fils déguisé en femme, et la f[il]le de la Rue de Canettes déguisée en homme, le tout par échange d’habits.” The family is reconciled and André is invited to dine with them on Mardi Gras. The seductress is named Mme Picard – her husband is “aux Judes” (is Jewish?). She has two children. He finds her interesting. She is not pretty but plump and graceful, with a pleasant smile, very pretty voice, and well-kept hands. All in all she seems quite “decent.” Nonetheless he remarks on the dangers or risks of the 18 year old “with a woman who seems fort gourmande.” He finally accepts the Mardi Gras invitation and ends up having a grand old time…. He “receives the son and Mme Picard “en femme”- i.e., André is disguised as a woman; the son is disguised as a Spaniard. Mme Picard’s sister is “a large child of a demoiselle who enjoys and uses her rights [of seduction?] and who sings very well though never opening her mouth.” Mme Picard loves dancing, as does the young man. They go off to the ball, and he goes to bed.

Current affairs are barely mentioned, although he frequently reads the papers in cafes. On 15 Jan. 1806 he “hears the peace treaty proclaimed” (by the town crier), probably the Treaty of Pressburg, concluded after Napoleon’s victory at Austerlitz. More to André’s taste are books. He reproaches his lover for not appreciating Justus Lipsius (!), picks up books along the quais, and records a few titles of books and pamphlets (La Gérocomie, Le Roi de Prusse, L’Aristocratie et la Democratie à Athènes, a pamphlet titled Ce qu’on dit des femmes et ce que j’en pense, and 3 acts of la Tragedie des Templiers (M. Raynouard, Les Templiers, tragédie, Paris 1805). The books accumulate, and periodically he tries to sell them to local booksellers. One night he attends the theater, thanks to one of Vuillemin’s clients, M. Cottu-Millon, who gets him a ticket to see the famous Mlle George in Corneille’s Horace. (Marguerite-Joséphine Weimer, called Mademoiselle George, 1787-1867, had been a mistress of Napoleon.) André lists the actors, who include George’s arch-rival Mlle Duchesnois, and records his impressions: Duchesnois is “horrible,” but “Mlle Georges est belle Belle, réellement Belle.” “Her voice, her gestures, everything pleases me, her mouth always accords with her face…. If she works to perfect herself, she will be the best of all actresses.… She was superb in the 3rd act when she wore no more rouge.”

Finally, André’s journal is filled with allusions to streets, places and neighborhoods of Paris. He lives in the sixth arrondissement, near the Luxembourg and the Boulevard Saint Germain, but he circulates throughout Paris, running errands or seeking work. Mentioned are the Pont Neuf, the Pont des Arts (where he goes once to see the high water in the Seine), the café on the corner of the Place de l’Odéon, the rue Notre Dame des Champs (where he visits his lover’s old apartment, thinking of “the terrible illness that she suffered there”), Montmartre (where he remembers times spent with her), the rue d’Assas, rue Jean Bart, rue de Seine, rue de Fleurus, the Louvre, the Place des Victoires, Place Louis XV (renamed the Place de La Concorde in 1795), the Tuileries, and the Luxembourg Garden, which is close to his home, but this hardcore Parisian only once mentions going there to sit under the trees, in the penultimate entry. Item #4158

No longer available