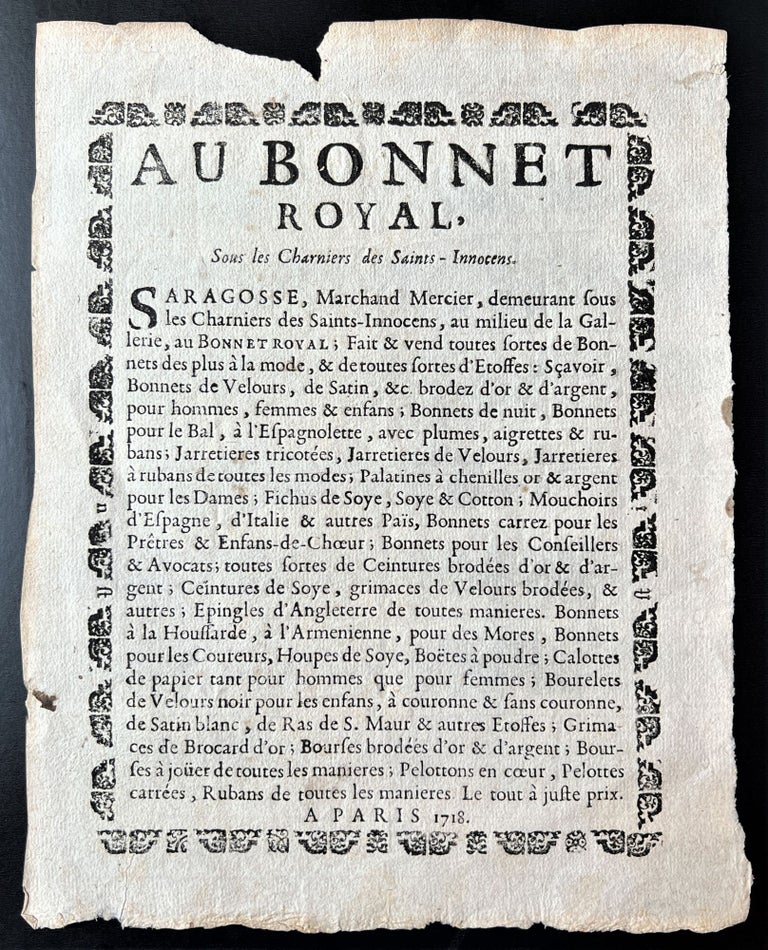

Au Bonnet Royal, Sous les Charniers des Saints-Innocens. Paris: 1718.

4to broadside (235 x 183 mm). Text within border of type ornaments and a few sorts (fl, n, i). Deckle edges. Slightly browned at upper margin, chip in upper margin not affecting text. ***

An unrecorded publicity broadside for a menu marchand mercier, a sort of haberdasher, offering hats, skullcaps, bonnets, ribbons, garters, purses, ribbons, belts, cases for face-powder, tufts and tassels, and other accessories whose purpose remains shrouded in the fog of fashion history.

One of the six codified corporations of merchants of Paris, it was said of the marchands merciers that they were “vendeurs de tout, faiseurs de rien” (Verlet, p. 11, citing the Encyclopédie), since, unlike the other corporations, they were forbidden from manufacturing and were purely vendors. Originally applied to merchants of textiles, carpets and related objects in the medieval period, the pleonastic term came to encompass an economically broad range of tradespeople, ranging from art dealers to vendors of ribbons and knick-knacks. The objects offered here belong to the latter category.

Like many of his fellow salesmen and -women of simple clothing and accessories, our advertiser, who identifies himself as “Saragosse,” marketed his colorful wares in a most unlikely spot: in the middle of the dank field between the charnel houses of the Cemetery of the Innocents (near les Halles), former site of the famous 15th-century mural of the Danse macabre (destroyed in 1669). Far from the opulent boutiques of the art-dealing marchands on the rue Saint-Honoré, this insalubrious and vile-smelling locale, notoriously dangerous after dark, had become the regular marketplace for the menus merciers, the lowliest representatives of the trade, as well as of public scribes; one row of charnel houses came to be known as the Charnier des lingères, and the other the Charnier des écrivains.

At Saragosse’s stand or shop could be found “the most fashionable bonnets, in all sorts of materials, that is, velvet, satin, embroidered with gold and silver, for men, women and children, night caps, hats for the ball, à l’Espagnolette [an elaborate head-dressing], with feathers & ribbons; garters: knitted, velvet, with ribbons; palatines [a neck ornament] and chenilles [caterpillar-like trimmings] in gold and silver for ladies; silk or cotton scarves; handkerchiefs from Spain, Italy, and other countries; square hats for priests and altar boys; hats for councilors and attorneys; gold- and silver-embroidered or silk belts and sashes, box pleats (grimaces) of embroidered velvet; English pins of all sort. Bonnets à la Houssarde [and four more kinds of hats, with their names]; paper skullcaps for men and women; bourrelets [rolled pads of fabric] of black velvet for [i.e., to protect] babies, bourrelets with or without crowns, in white satin ... & other materials [as hair ornaments for women] ... gold- and silver-embroidered purses,” etc., “all at fair prices.”

I locate no other copies of this informative broadside. Cf. P. Verlet, “Le commerce des objets d'art et les marchands merciers à Paris au XVIIIe siècle,” Annales. Economies, sociétés, civilisations 13, 1 (1958), pp. 10-29. Item #4157

No longer available