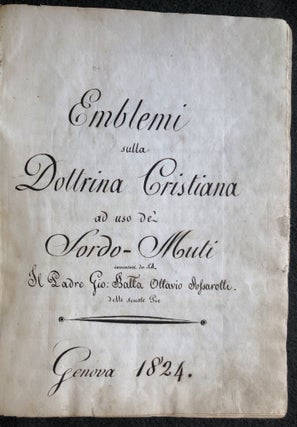

Emblemi sulla Dottrina Cristiana ad uso de' Sordo-Muti. Genoa, 1824.

Manuscript on laid paper, 4to (236 x 176 mm). 126 leaves, foliated [3], 1-3, [1], 4-42, [1], 43-51 [1] 52-61 [1] 62-103 [1] 104-118 (complete). The numbered leaves containing one hundred and eighteen emblematic drawings, all full-page, explanations written on versos, the unnumbered leaves containing the title, 3 and 1/2-page introduction, and section titles; most of the illustrations in landscape format. Calligraphic title, text in brown ink in a neat cursive hand; the drawings in graphite, pen-and-ink and gray wash, a few with details in brown ink, each within rule border with numbering at top (gutter edge). Corner repairs to ff. 1-10, tears into ff. 9 and 104, a few other short marginal tears or fraying to edges, ff. 100 and 101 with gutters reinforced on versos, occasional minor offsetting or soiling. Late 19th-century half parchment and brown glazed paper, manuscript title label on spine.

An illustrated manuscript course of religious instruction for Deaf children by a pioneer of Deaf education in Italy, using an original emblematic visual “language.”

By the early nineteenth century, pre-modern misconceptions concerning the learning abilities of Deaf children had been largely exposed as false by such eighteenth-century pedagogues as the abbé Sicard and Charles-Michel de l’Epée in France, each of whom founded schools for the Deaf and contributed to the development of a standardized sign language, or Samuel Heinicke in Germany, who implemented a different method of communication for the Deaf, centered on oral speech. In Italy, the most influential figure in the education of Deaf children was Ottavio Assarotti. As a young man Assarotti entered the order of the Piarists (the Scuole pie). Founded in 1617, the Piarists’ principal mission was (and remains) the provision of free education to poor and especially disabled children. After several years teaching theology and philosophy, Assarotti set those disciplines aside to devote himself full-time to the development of an instructional program for Deaf children. Assarotti’s method consisted in teaching the children not only reading, writing, and sign language, but also a full range of humanist disciplines, including science, the arts, and foreign languages. In 1805 he obtained financial support from Napoleon to found a school, which after some delays was finally opened in 1811 in the former Bridgettine convent. After Napoleon’s defeat, the growing school received renewed support from King Vittorio Emmanuele I, and its fame spread throughout Europe.

“Assarotti made great use of sign language in his teaching ... Directors of nearly all Italian institutes for deaf students flocked to learn from him and carried his method back with them. Pope Gregory XVI sent the new directors of the Rome Institute, Padri Ralli and Gioazzini, to study in Genoa with Assarotti. Upon their return to Rome, they too used his techniques. How is it possible that a man so renowned and successful in his own time did not earn so much as one line of recognition in the historical accounts of other countries? Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that Assarotti left no traces in written form of his philosophy and method. Had he done so, not only would he have gained respect and notoriety outside Italy, but perhaps the critical events soon to follow [the subsequent dominance of “oralism” over sign language in Italy] would have taken a different course ...” (Radutsky, p. 245).

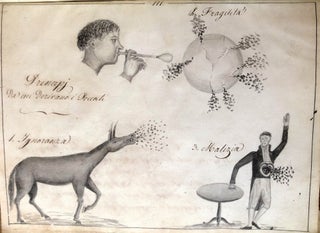

In fact, Assarotti wrote and may have published several texts for his pupils (listed in DBI, but not found in OCLC or ICCU). The present unpublished work was probably prepared for the use of instructors in the school. It contains a pictorial religious course of instruction, using a complex but precise symbolic system to explain Christian doctrine and liturgy, including the most abstract theological concepts. All the elements in the drawings are identified in captions of varying lengths and in various layouts. Names or words are often incorporated as visual elements of the emblems. While somewhat primitive, the drawings’ unique iconography is evocative, and some have a powerful, dreamlike quality.

In the Middle Ages the Deaf were barred from the sacraments – and hence from marriage and any kind of normal life – because of the belief that they could not understand the word of God. While these strictures were loosened in 1571, thanks to Luther’s influence, prejudice against Deaf persons’ abilities to achieve salvation subsisted, partly because it was thought that they could not perform Confession. Hence the importance to early educators of the hearing-disabled of providing their pupils with comprehensive religious instruction, as an essential foundation of their integration into society.

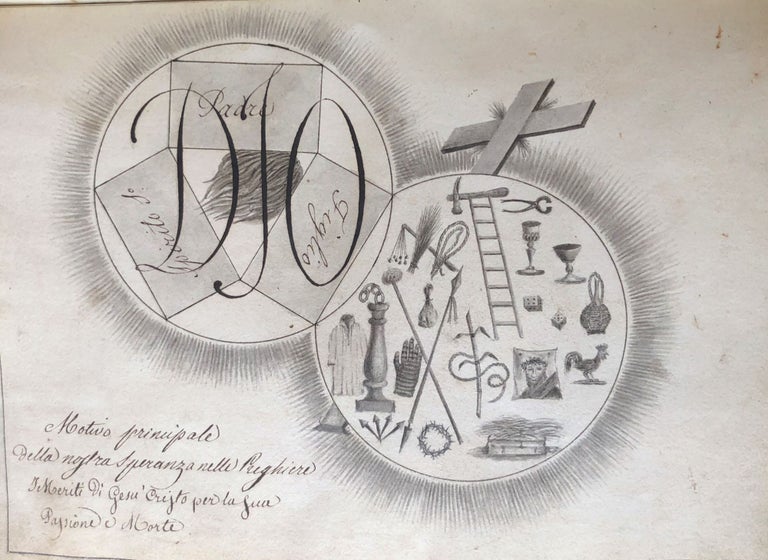

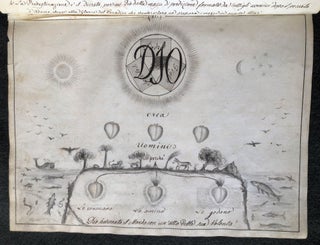

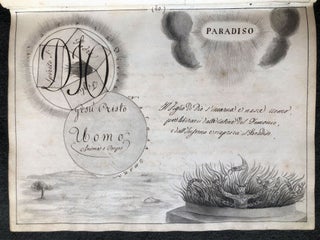

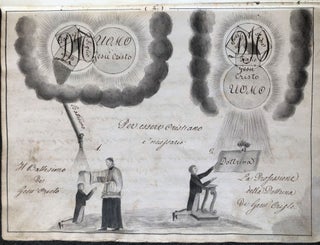

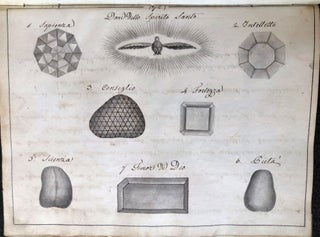

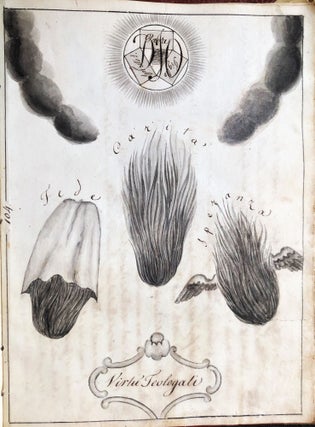

The unnamed author of the introduction, writing in the third person, describes Assarotti’s school and praises his religious zeal, humanity, and his understanding that Deaf people, who had been previously “abandoned by society,” are fully competent and indeed capable of the highest intellectual and spiritual attainment. The emblems (the author explains), will present to the Deaf student an easy transition from familiar material objects to those objects which are less material, and from there to the most immaterial concepts of all. In doing so he or she will eventually absorb the entire Christian doctrine. The figures are described as Assarotti’s own (egli ... ha inventato le figure, che formano questo Libro ...), but whether the actual drawings are in his hand is uncertain. The introduction concludes with an explanation of the most frequently recurring emblematic figures. God is represented by a circle containing three rectangles which touch the circle and each other, representing the Divine Trinity: flames emanate from the God the Father and Jesus rectangles toward the one representing the Holy Spirit, a concept which is explained (in the text) as the reciprocal love between the two other Divine Persons. Jesus the man (as opposed to his divine nature) is shown by another circle, helpfully inscribed “Uomo / Jesu’ Cristo,” and humans or human souls are represented by hearts (although the meaning of the heart emblem varies throughout the manuscript). Further symbols, introduced later, are explained on the versos of the drawings.

Contrasting with the approbation granted his pedagogical achievements, Assarotti’s religious views, linked to the most mystical wing of the Ligurian Jansenists, met with resistance from the church hierarchy, and some of his theological writings were not approved for publication. The drawings of this manuscript provide a glimpse of an abstract mysticism which would certainly have been at odds with Catholic orthodoxy.

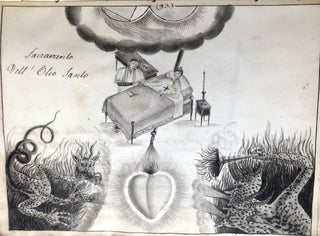

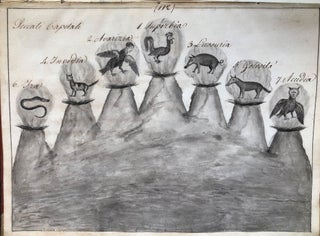

The work is in five parts, titled: Faith (Fede, ff. 4-42); Laws (Legge, 43-51); Prayer (Preghiera, 52-61); Sanctification (Sanctificazione, 62-103), and Virtue (Vertù, 104-118). The first part is a visual exposition of the Credo, starting with God’s attributes: his ubiquity is represented by the God and Jesus circles overlapping above a symbol of the world (earth and heavens), with the word DIO written repeatedly across the page; his omniscience by the God symbol at top sending down rays of light, at center a man sitting under a tree, and below that a well, captioned “Abyss.” Creation is a delightful drawing of fish in the seas flanking a mound representing the earth, on top of which cavort animals under trees, and within which are three large hearts, linked to a central pole at the top and illustrating the three reasons that God created man: so that they might know, love and enjoy him. The Church of Jesus Christ is an architectural drawing of a fortress. Heaven is a light emanating rays, while Hell is a large vat whose opening is locked and barred. Virtuous souls are flaming hearts each with an open eye (since they see God); sinful souls are spotted hearts with wilted stems instead of flames. These blemished hearts recur throughout the book, for example behind bars in the vat of Hell; enchained by a similarly spotted Devil; in a genealogical tree descended from Adam and Eve; or clustered above Hell on Judgment Day, opposite a crowd of pure, haloed hearts, trumpets sounding above and lightning striking the damned while divine light bathes the saved.

The section on Laws contains various allegorical representations of the Ten Commandments. While some drawings amount to schematic tables demonstrating the relationships between theological concepts, others are more pictorial. Reflecting no doubt Assarotti’s personal mysticism, all aspects of the divinity are abstract: there are no angels, Madonnas, or images of Christ. Crosses are shown, but there are no Crucifixions, and Christ’s Passion appears as a circle containing the Arma Christi. The church hierarchy is represented by a papal tiara, mitres, and stoles. Human figures appear predominantly in the drawings of the sacraments and in representations of sin. In contrast with the invisibility of the divine, Satin is personified as a grimacing devil, and the seven deadly sins appear as animals and monsters poised above poisonous emissions from Hell’s chimneys.

That Assarotti’s school used such manuscripts for teaching is supported by the existence of another manuscript, very similar in content, but lacking the title and two leaves, offered by the Austrian antiquarian book firm Inlibris. Cf. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, art., Antonella Dolci, 4:433-4; E. Radutsky, “The Education of Deaf People in Italy and the Use of Italian Sign Language,” in Van Cleve, ed., Deaf History Unveiled (1993), 237-5; Rauthgundis Kurrer, Gehörlose im Wandel der Zeit (doctoral dissertation, University of Munich, 2013, available as a pdf online), pp. 30-33.

No longer available

Status: On Hold