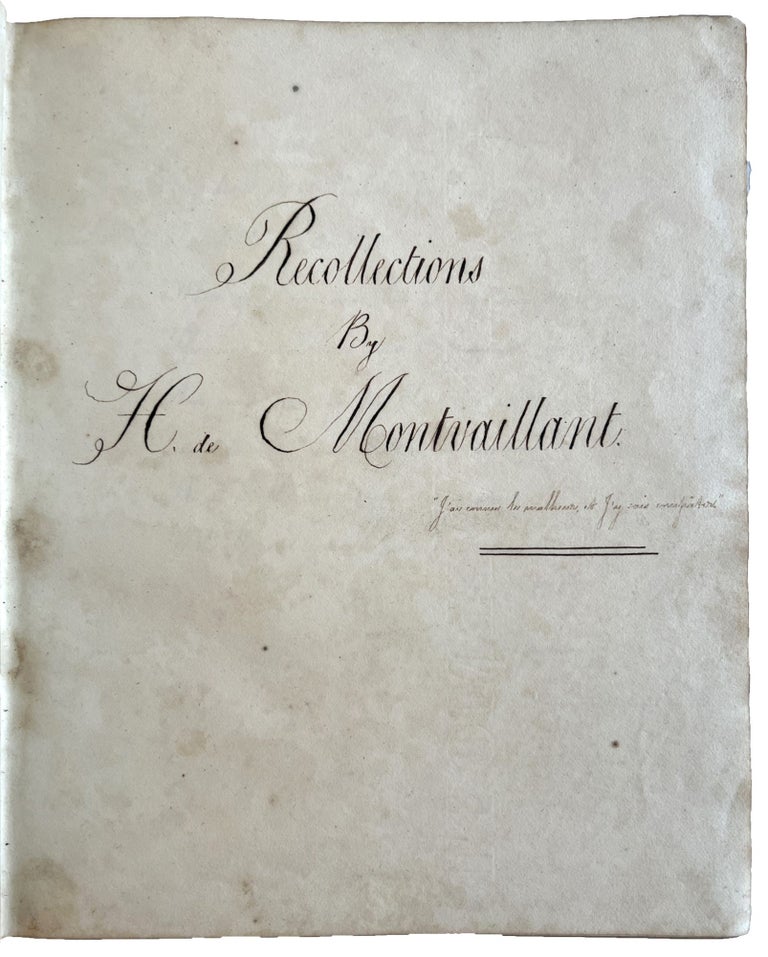

Manuscript memoir of a French officer's experiences during the Napoleonic Wars in Spain, 1808-1809. Title: Recollections / By / H de Montvaillant. [Hunthill House, Scotland, 1814].

Written in English in a small and narrow but legible italic hand, with occasional corrections or additions in a different hand, on wove paper watermarked Budgen & Wilmott / 1812. Four unnumbered pages of French text at front and four at back, the latter dated 27 May 1814, in a different hand, apparently the author’s, on different paper with no visible watermark. Very good; some occasional spotting. Contemporary red straight-grained morocco, gilt edges (scuffed and scraped, joints strained, head of spine chipped).***

A first-hand, unpublished memoir, filled with searing descriptions of the horrors of war, by a French army officer, veteran of the terrible Peninsular War. The narrator was one of few survivors of the surrender of French forces after the Battle of Bailén in July 1808. The background to this event was Napoleon's attempt to complete the isolation of England from the continent by sending a French army into the Iberian Peninsula to seize the coast of Portugal and occupy Spain. Napoleon later referred to the Peninsular War, characterized by appalling cruelty on both sides, as the ‘Spanish ulcer’; it was to be one of the primary factors in his downfall.

General Pierre Dupont de l'Étang was charged with securing French control of the major cities in Spain. Dupont's 20,000 men had initial success, but as they penetrated deeper into Spain they faced increasing resistance. This memoir, by H. de Montvaillant, an 18-year-old Protestant officer from Montpellier who was serving in the second Corps d’Observation of the Gironde, recounts the route and experiences of Dupont's army to its furthest point of penetration into Spain: Córdoba. There, after a particularly bloody and cruel occupation, the army was forced to withdraw and was soon overwhelmed. Dupont surrendered his army at Bailén. Originally promised safe passage, most of the French were slaughtered immediately after their surrender.

Montvaillant’s account commences with the French arrival in Bayonne in November 1807. By December 22 the French troops had arrived in the town of Vittoria (50 miles west of Pamplona), and by January 9, 1808, they had advanced to south of Burgos. Detailed descriptions of the monuments, churches, libraries, art, and inhabitants of various localities passed through in their zigzagging progress south through French-occupied Spain enliven this first part of Montvaillant’s narrative: he describes with evident pleasure Burgos, Valladolid, Guadarrama and the Escorial, Madrid and Toledo, where the troops spent most of May. He makes the acquaintance of many Spaniards. In Toledo a young woman explains to him the contradictions of Spanish women, rendered emotionally susceptible by their extreme religious devotion, but whose sometimes shocking (to the French) frankness contrasts with a strict sexual morality (pp. 75-76). Later he deplores the time wasted in Toledo while the Spanish insurgents were building up their strength.

As the French troops proceed southward, the local populations exhibit increasing hostility, often hidden under exaggerated politeness. They encounter a Frenchwoman who has fled Bailén, saying that she was not safe there because of her nationality, but the soldiers assume that she exaggerates. By the end of May the French pass the Sierra Morena and enter Andalusia, and the truth becomes evident. It is at this point that the narrative takes on an ominous tone. Montvaillant notes that the population had abandoned the villages, taking all foodstuffs. He records that the senior officers had assumed that the army would only be harassed by small bands of “brigands,” a far cry from the massive insurgency that it encountered: “We learned that the insurgents each day gathered strength, and that the Junta of Seville was determined to stop us in our March. The following day we got to the little town Baylen, in whose plains two months afterwards our destiny was decided” (p. 86).

The first battle was engaged at Acoléa, just upstream from Córdoba, an event Montvaillant described in a poem (in French, transcribed). The next day the French arrived at Córdoba, where the Spanish enemy had taken refuge. A musketry attack upon their arrival so enraged General Dupont that “he gave up the town to pillage”” (p. 88). Allowed to run wild, the French soldiers sacked the city, committing hideous crimes: “Neither tears, promises, or humble supplications could arrest the thirst for pillage...” (p. 89). Discipline was nonexistent, drunkenness and looting continued for eight days. The soldiers raped the women and ransacked homes. Montvaillant presents himself as a savior of women and the elderly on several occasions, but notes that some of the Spanish whom he and fellow officers placed under protection in Córdoba were later “the first to persecute the unprotected French prisoners, and even those who had been their Benefactors” (p. 92). While he does not detail the contents of the soldiers’ plunder, it is known that the rich churches of Córdoba were heavily looted. Notwithstanding the circumstances, he manages to visit, and describes in amazement, the great mosque-cathedral, scarcely changed in a thousand years.

Nine days after the French entrance into Córdoba, Montvaillant and his troops were ordered back to Alcolea to guard a bridge crossing. En route there from Cordóba he discovered, and describes in gory detail, the many mutilated corpses of the French sick and wounded who had been left along the line of march while the main body of General Dupont's troops had taken Córdoba. “It is almost incredible how people calling themselves Christians could push inhumanity to such an excess” (p. 96).

The army moved back to Andújar, near Bailén, and encamped. Montvaillant records that the general staff had by now realized that the French were now outnumbered and that the opposition had organized itself. Dupont's army was isolated, without hope of reinforcement or re-supply, defending a garrison situated on a flat plain in the scorching sun. The narrative is now of revenge, heat, troop dispositions, losses, tactical mistakes, errors of the general staff, and increasing difficulties. Dupont's surrender came on July 20, 1808.

The officers were segregated from the defeated army before being escorted, supposedly to return to France. Most of the army was slaughtered within days. Montvaillant records the details of his months-long “death march” southwards to the coast, finally arriving at Jerez de la Frontera (near Cádiz) to await embarkation to France. They waited in vain. Their captors kept them in Jerez, having discovered that the ruling Junta of Seville had abrogated the surrender treaty, and that the inhabitants were waiting to massacre them on their approach to Cádiz. Montvaillant’s account is henceforth devoted to many anecdotes of captivity, and of the prisoner’s horrendous treatment at the hands of their escorts and guards. He is unclear as to exact dates, but it seems that the French captives were held at Jerez until mid-December and then hastily driven aboard ships to sail for the Balearic Islands (p. 141). A severe storm intervened, and they were blown off course to Africa, finally coming to port at Gibraltar; several days later they were blown back to Andalusia, at Málaga. After more storms and much sailing (having been at sea 25 days for a voyage which normally took a week - p. 147), they finally made the Balearics.

Here the worst surprise awaited: the desert island of Cabrera. Montvaillant counts some 4000 surviving soldiers and 400 officers who were forced to survive as best they could on this scorching hot, nearly waterless, uninhabited island (p. 148). (Details of his account square with Denis Smith’s monograph on the subject.) During the next 4 years close to 9400 French prisoners of war were exiled on this island; possibly 40% died, of disease or malnutrition. Montvaillant was one of 216 officers who were collected from this exile after a month and taken to the capital, Palma. There, imprisoned in better circumstances, this group of officers waited; nearly half would be massacred during a riot and assault on the prison by the inhabitants of Palma. By March 1809 only 140 of the original 250 rescued officers were alive, among them Montvaillant. They were returned to Cabrera, where the living conditions were desperate (pp. 155-165). Despite this, the officers were able to conjure up distractions. He describes theater productions and dances, and the jealousy and bickering among those playing female roles in these performances, commenting that the theatrical chronicle of Cabrera would make quite a book.

Eventually, the officers were placed aboard an English ship. On August 4 they were off Cape Palos (near Cartagena) where there were rumors of a prisoner exchange. It did not occur. Montvaillant and his companions spent several weeks aboard the English ship and were finally delivered to Portsmouth. He went on to Salisbury for a short time and then embarked again for Leith en route to his final destination in Scotland, where he remained in exile until the accession of Louis XVIII in 1814.

The text is written in an occasionally stilted English, a translation from the author’s own French account, by a family whom he had befriended at Hunthill House, near Jedburgh, Scotland, where he stationed. Eight pages of notes in French by the author are inserted, four pages at the beginning (the bifolium is inserted using wax seals) and four pages at the end, dated May 27, 1814. The French preface contains a romanticized account of the author’s Scottish sojourn. Following the narrative, in a letter to his family, dated from Jedburgh, 27 May 1814, Montvaillant explains the history of the manuscript (the remaining pages contain literary notes including translations into French of poems by Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott). During his years of exile in Jedburgh Montvaillant had become deeply attached to the owners of Hunthill House, and to their three daughters. Without them, he claims, he would not have survived the loneliness of his exile. In homage and gratitude, he dedicated his memoir to them. His friends retained the original French version as a keepsake of their friend and an engrossing biographical narrative, and presented him with this translation, which he brought back to France, planning to render it anew into French, to share with his family and close friends. He emphasizes that he plans to keep the manuscript unpublished; perhaps the memories were too painful.

Cf. Denis Smith, The Prisoners of Cabrera: Napoleon's Forgotten Soldiers, 1809-1814 (New York, 2001). Item #2677

Price: $8,800.00