Paravent de six feuilles. Augsburg: Johann Jacob Haid & son, [ca. 1740].

Six tall narrow folio-sized engravings with etching (platemarks 400 x 207 mm., sheets 435 x 277 mm., deckle edges), unsigned but by Jacop Wangner after Watteau, numbered 1-6 in the plate at lower right, imprint at lower right I. Haid et filius, excudit A. V. [Augustae Vindelicorum]. Upper edges archivally tipped to mats. Fine.***

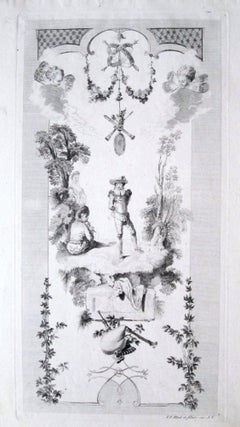

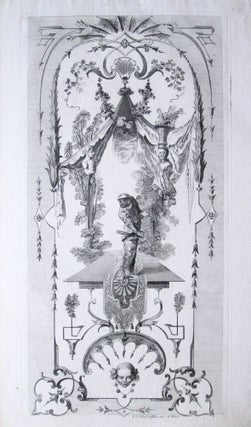

A perfectly preserved suite of six large rococo engravings reproducing Watteau’s paintings for a folding screen, intended to be cut out by ladies for use in furniture decoration.

Watteau’s influence on 18th-century decorative arts throughout Europe, by way of the many engravings after his work published by Gersaint, has long been recognized, but the use of the engravings as actual sheets to be cut up and applied to household objects has garnered little attention until recently. The vogue for decoupage probably first appeared in the late seventeenth century, and by the 1720s the hobby of cutting out colored prints for application to various household objects and pieces of furniture was all the rage, in France, Germany, and beyond. The process, which remained a favorite pastime throughout the eighteenth century, was known as la découpure in French, as Ausschneidekunst in German, and as lacca contrafatta or lacca povera in Italian, although “the latter term appears to be a true misnomer, considering the amount of minute work involved” (Kisluk-Grosheide, p. 83). It consisted of neatly cutting out hand-colored engraved or woodcut motifs or figures, applying them to a textile or sometimes cardboard ground, and varnishing them. These creations were applied to furniture, as well as to “screens, folding screens, wall hangings, ceilings, the tops of coaches, and sedan chairs” (loc. cit.), affording a passable imitation of Asian lacquer. The craze, which created a goldmine for certain print publishers, reached the point that bibliophiles and collectors were warned to keep a vigilant eye on their most precious books, prints and paintings, lest eager young ladies attack them with scissors.

In 1728, six engravings after Watteau’s paintings for a folding screen were commissioned by the art collector Jean de Julienne as part of a vast program of reproductions of Watteau’s painted oeuvre. They were engraved by Louis Crépy fils and published by the Paris marchand-mercier, art dealer and print publisher Edmé-François Gersaint. An announcement of their upcoming publication in the November 1727 Mercure de France explicitly described them (and two other Crépy-Watteau engravings) as “marvelously appropriate for decoupages, with which ladies these days make such pretty furniture” ([Crépy] grave actuellement six morceaux en hauteur .... d’après un Paravant peint par Watau, dont les compositions sont très-galantes. De pareils sujets peints sur des fonds blancs, conviennent à merveille aux découpures, dont les Dames font aujourd’hui de si jolis meubles (Mercure de France, 1 Novembre 1727, p. 2492 [digitized on Gallica]). Indeed, the publisher himself highlighted this usage in his own note in a later issue of the Mercure (cited by Glorieux, p. 212): pointing out that all of the decorative motifs in the Watteau engravings were “most useful for painters, fan-makers, sculptors, goldsmiths, tapestry-weavers, embroiderers, etc.,” he added that “all these ornaments can be perfectly used in decoupage” (tous ces ornements réussissent parfaitement en découpure).

These and other rococo engravings were quickly taken up by German publishers, especially in Augsburg (Metken, p. 102). This paravent (folding screen) suite was one of the first of the Watteau engravings to be copied in Germany. The present very close reverse copies of Crépy’s six plates appeared in Augsburg only a few months after their publication, in June 1728, in Paris: engraved by Jacob Wangner (or Wagner, ca. 1703-1781), they were published by the heirs of Jeremias Wolff in 1729. This set is an otherwise unrecorded reissue of the Wangner copperplates. A lavishly decoupage-decorated secretary in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art includes cutouts that were almost certainly from these Augsburg plates, as they are from “reverse copies of the prints by Crépy” (Kisluk-Grosheide, p. 88, noting other examples of Augsburg copies of Watteau prints used on the same secretary). Her assertion that “it has not been shown that these engravings were actually used for this purpose” (p. 84) is only applicable to the French plates. Indeed, other examples of lacca povera objects described in her article point to the German production of copies of French rococo prints as the main source for decoupage at this time, on pieces produced throughout Europe, including in Italy and in France itself.

The general title appears at the foot of the first plate. Each engraving presents a central figure or scene set within a frame of delicate rococo arabesques and ornaments. Three show the Comédie italienne figures of Pierrot, Harlequin, and Colombine (a woman playing the lute) on a rug-bedecked stage, a pair of allegorical figures flanking an awning above, and at bottom the smiling visage of a Commedia dell’Arte character of the opposite sex. The remaining pastoral scenes of courtship or douceur de vie are set within naturalistic elements, two with streams flowing over a dripping shell-shaped basin or ledge under which a ghostly face can be dimly discerned. Watteau’s designs were based on earlier designs by Claude III Audran, decorative painter for Louis XIV at Versailles and Fontainebleau, to whom Watteau had apprenticed. “After joining forces with ornamentalist Claude III Audran about 1708, he [Watteau] began inserting figures in Comédie-Italienne costumes into Audran’s trademark arabesques” (Judy Sund, “Watteau’s Pierrots, Why so Sad?,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 98 , no. 3, 2016, p. 325, reproducing the Pierrot panel from the present series).

OCLC locates a single copy of the Wolff issue, at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (reproduced in Gallica). In the present issue, of which I locate no other copies, the engraver’s signatures were removed.

On the Wolff issue, cf. W. Augustyn, “Augsburger Buchillustration im 18. Jahrhundert,” in Augsburger Buchdruck und Verlagswesen von den Anfangen bis zur Gegegenwart (1997), p. 820 (citing E. Isphording, Gottfried Bernhard Göz, 1708-1774, 1997, pp. 35 ff.); Thieme Becker 35:150. On the Crépy engravings, cf. Guilmard, Maitres ornemanistes, p.145; Dacier & Vauflart, Jean de Julienne et les graveurs de Watteau au XVIII. siècle, 159-163; E. de Goncourt, Catalogue Raisonné de l’Oeuvre ... d’Antoine Watteau (1875), p. 224, nos. 309-314; G. Glorieux, À l'enseigne de Gersaint: Edme-François Gersaint, marchand d'art sur le Pont Notre Dame (Paris 2002), pp. 189-192; Mark Millard Collection: French Books, no. 170.35 (5 of the 6 plates). On the use of these engravings for decoupage, see: D. O. Kisluk-Grosheide, "'Cutting up Berchems, Watteaus, and Audrans': A Lacca Povera Secretary at The Metropolitan Museum of Art," Metropolitan Museum Journal 31 (1996), pp. 81-97; and S. Metken, Geschnittenes Papier (Munich, 1978), pp. 101-2 & 113. Item #2420

Price: $8,000.00